Today we are introducing an article ‘When Silence Speaks: Press Censorship and Rule of Law in British Hong Kong,1850s–1940s’ by Michael Ng, The University of Hong Kong.

‘’Who is to say that the danger has passed? The greater part of the danger may have passed but some of it may have remained.’’

It may seems familiar in today Hong Kong, however, this comes from 1931 British colonial Hong Kong’s Central Magistracy. In February 1931, four vernacular newspapers (Wah Kiu, Nam Keung, Nam Chung, and Chung Hwa) were together prosecuted for breaching the Newspapers Regulations under the Emergency Regulations Ordinance by publishing a series of news reports on protests and strikes amongst prisoners in Victoria Gaol without the prior consent of government censors.

The trial hearing, which attracted considerable public discussion, was held at the Central Magistracy and widely reported in both the Chinese and English press. the defendants’ counsel, F. H. Loseby, before calling witnesses (including the government censor responsible for censoring the newspaper articles in question) for cross-examination, questioned the applicability of the Newspaper Regulations in peacetime Hong Kong. In the event that they were inapplicable, he averred, the charges should be dropped. He also submitted that the use of emergency regulations once times of danger and emergency has passed was a gross abuse of power. The prosecution, in contrast, insisted on the statutory interpretation that the regulations remained in force until repealed by the Governor, and said the sentence in the first paragraph.

Protests against the censorship of Chinese newspapers continued until the outbreak of World War II, and the arguments between the Chinese community and the colonial government were not confined to courtroom debates. In 1928, the leading Chinese newspapers in Hong Kong filed a joint petition with the Secretary for Chinese Affairs for the lifting of the censorship system, albeit without success. In July 1936, fifty editors of Chinese newspapers in Hong Kong submitted a jointly signed letter to Lo Man Kam, a Chinese legislative councilor, requesting that the matter of censorship be raised in the Legislative Council, which Lo duly did in the Legislative Council session on August 26, 1936, proposing a motion standing in his name that the censorship of Chinese Press should be abrogated.

The Colonial Secretary, representing the Hong Kong government, responded, making it clear that the administration’s anxiety justified the continuation of stringent censorship of the Chinese press. In a rebuttal of Lo’s arguments, he spoke of the public danger outlined in the Emergency Regulations Ordinance: That danger exists still, and will continue to exist until a definitely stable government exists in China. [… T]he welfare of Hong Kong depends on good relations with her customers in trade and […] nothing will sooner prejudice those relations than an impression that the Colony can with impunity be made a base from which to foment disorder. […] None will defend interference with the reasonable freedom of the press. [… However,] so long as unrestrained publication can do very serious injury to our relations with China, and with other friendly Powers and so to the Colony itself, just so long is prevention better than cure. We can see similar mindset appearing in today Hong Kong Court too.

Lo rose again to rebut the Colonial Secretary’s notion that prevention is better than cure: If the Chinese Press is to have only a measure of the freedom of the Press while that definition of public danger exists, then I feel that I for one will not live to see the day it is free. […] If you are going to give freedom to the Chinese Press only at a time when there is an idealist state, blissful inertia and benevolent governments without armaments, then I say to you, Sir, don’t give it, because there will be nobody in this world to enjoy it!

Michael Ng’s article reveals how the press, the Chinese press in particular, was continuously and systematically monitored and pervasively censored through the collaborative efforts of executive actions, legislative provisions and judicial decisions, this article further posits that the common law system practiced in British Hong Kong during the period under study was complicit in the imposition of an authoritarian form of law and order, and was more interested in preserving the British Empire’s overseas territorial and economic possessions and managing the power equation in the region than in safeguarding individual liberties in Hong Kong. Hong Kong is often praised for its rule-of-law colonial legacy, but this article argues that such narrative does not stand up to the scrutiny of archival study. The English law in Hong Kong history, rather than constituting a lens through which one can witness Hong Kong’s quest for modernity, is more akin to a mirror reflecting an ongoing cycle of coercion and resistance through law. Drawing on unexplored archival sources, the article first discusses how the colonial government used libel lawsuits to punish the press for criticism of the government in the 19th century, before turning to describing in detail the daily mandatory vetting of Chinese newspapers by colonial censors under the office of the Secretary for Chinese Affairs and related prosecution cases in the early 20th century.

「公安風險千變萬化,加上現時國際關係複雜。雖然最壞情況已經過咗,但潛伏力量隨時都會捲土重來,危害本地安全、破壞社會安寧。」

(Who is to say that the danger has passed? The greater part of the danger may have passed but some of it may have remained.)

以上使用「當代語言」翻譯的說法,經常出現在現今香港新聞。

事實上,這段說話來自1931年英殖時期的香港法院。1931年2月,包括《華僑日報》在內的四份本地報章被控干犯《緊急情況規例條例》(又稱「緊急法」,Emergency Regulations Ordinance)下關於境報刊的條文——在未經政治審查同意前,刊出一系列域多利監獄囚犯抗議和示威的報導。

審訊於中央裁判司署進行,受公眾觸目,多家中文及英文報章都有報導。辦方律師F.H. Loseby在盤問證人(包括負責審查報刊的政府審查員)前,向法官質疑報刊條文不適用於和平時期的香港,他說如果不適用,控罪就應被撤銷。Loseby進一步說,當風險與緊急情況已過時仍然使用緊急法是嚴重濫用權力。反之,檢控方強調此法一直生效直至港督廢除,然後說出了文首那段說話。

對中文報章審查的抗議持續,直至二戰爆發。殖民地政府與中文社群的爭論並不限於法庭,1928年,香港主要的中文報章向政府發起聯合請願,要求廢除對中文報章的審查制度,無果。1936年7月,50名香港中文報章編輯向時任華人立法局議員羅文錦遞交聯名簽署信件,希望他在立法局內提出廢除審查制度的議案。同年8月26日的立法局會議上,羅文錦提出議案,輔政司回應指「危機依然存在,直到中國有穩定的政府。香港的福祉取決於與其貿易客戶的良好關係,而如果殖民地提供外界一個煽動暴亂基地的印象,這會危害前述關係。無節制的出版會嚴重傷害我們與中國,以及與各國友好列強的關係,所以預防勝於治療。」類似的語言及思維也見諸今天的香港法庭。

羅文錦反駁這種預防思維(意譯):

「如果中文媒體要在這種社會安全的定義下有丁點出版自由,我想我有生之年都不會見到自由的那天。如果你們只會在理想狀態、國家仁慈、無差異無戰事的世界大同下,才賦予中文媒體出版自由,那我只能夠說,閣下,你不要給予好了,因為那將永不有人可以享受這些自由!」

吳海傑這篇文章旨在揭示英國在殖民地香港首百年的出版審查。報章,特別是中文報章,長期被行政、立法、司法機關系統性監視及審查。所謂的殖民時代新聞自由不過是個神話,經不起檔案研究的考驗。相較於人權自由,英國殖民政府更在意的是如何促進帝國海外領土與經濟利益,以及維持地區勢力均衡。英國法律在香港,與其說其作為看待香港如何走向現代化的視野,不如說反映其如個成為持續壓逼與反抗循環的工具。這篇文章首先討論十九世紀殖民政府怎樣使用誹謗訴訟去懲治傳媒,繼而談到二十世紀政府強制審查中文報章的仔細情況和相關檢控。

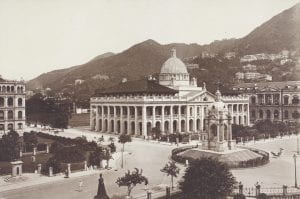

Image courtesy of Hazell, Denis H. and Historical Photographs of China, University of Bristol

https://hpcbristol.net/visual/Bk09-10