We are pleased to have Dr. Andrew Hillier writing for us this week. After completing his PhD at the University of Bristol, Andrew is now an Honorary Research Associate at Bristol and regularly contributes to the University’s Historical Photographs of China project. Andrew has recently published his book Mediating Empire: An English Family in China 1817-1927 (huge congratulations Andrew!). He has kindly accepted our invite to write a blog post, in which he reflects on the impact of Hong Kong on three generations of his family.

Family and Memory in Old Hong Kong

‘Why didn’t I ask more about the family and the time it spent in Hong Kong and China?’ How often have I asked myself this question? However, in this post, I want to consider, not what I should have asked, but what earlier generations may and may not have asked about their forbears and their lives in Hong Kong. What they knew and what they were told will have informed the family’s collective memory, a memory that can be found embodied in their letters, photographs and surroundings and which, in turn, shaped their mind-set on both a public and private level.

In 1895, Harry Hillier (my great- grandfather) was appointed Acting Commissioner of Imperial Maritime Customs (IMC) for Kowloon, and this was officially confirmed the following year. Although the Customs Stations were positioned on the China coast, the Commissioner was provided with a fine new residence on the Peak and there, for four years, Harry lived in exclusive luxury with his wife, Maggie, and four children – Eddie, his daughter by his first marriage, a second daughter, Dorothy, and two sons, Harold, my grand-father (born in 1892) and his younger brother, Geoff.[i]

This was not the first time Harry had lived in the colony. He was born there in February 1851 but the following year, his father, Charles Batten Hillier, the Colony’s Chief Magistrate, and his mother, Eliza, came to England, bringing with them Harry and his two elder brothers, Willie and Walter. When they returned to Hong Kong, the three boys were left to be cared for by a relative in Cambridge. But, if Harry had no actual memories of Hong Kong, he will have learned much about his parents’ life from the letters they wrote to him and his brothers, some of which still survive, and, later, from talking to his mother when she returned to England, following his father’s death in 1856.[ii]

We can get a good idea of the picture Eliza will have painted from the cache of letters, which she wrote to her sister, Martha, during her time in Hong Kong and which also still survive. Found in her papers when she died, they describe the colony’s early days when English families were beginning to settle and carve out a life, insulated from the teeming Chinese world on their doorstep, a genteel setting in which notions of imperial superiority and racial difference were already being forged.[iii]

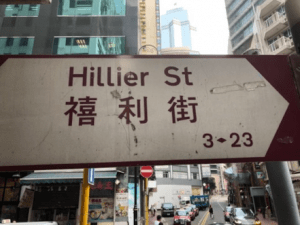

If these helped shape Harry’s mind-set, there were also two memorials which embodied his parents’ life in Hong Kong, one, very public, the other, intensely private, and both of which can still be found today. Hillier Street had been named as a parting gift by Governor Davis when he left in 1848, loathed by almost everyone, but not, it seems by Charles and the street remained an important family memorial.

Although his appointment as the colony’s Chief Magistrate in 1847 had come as ‘a bolt from the clouds’, and, over the next nine years, he would be subject to much criticism, when the time came to leave, he received fulsome plaudits for the way he had performed his duties. How much of this Harry will have learned by the time he arrived, we cannot know. Certainly, his mother will have focussed on the positive side and the colony will have been keen to forget this unhappy time in its history, which had culminated in the zealous but unbalanced Thomas Chisholm Anstey accusing almost all its officials, including Charles, of corruption.

However, Harry will certainly have learned about his father’s work shortly before he left, because it was then that James Norton-Kyshe published his monumental History of the Laws and Courts of Hong, with the first volume containing over one hundred references to Charles Hillier. If many were unflattering of this ‘noted flogger’, the final verdict, as delivered by the China Mail, was that, because of Charles’ ‘intimate knowledge of the Chinese language and Chinese customs, the Chinese would be unlikely to have again a Magistrate from whom they will receive as much justice’.[iv]

The second and intimate memorial is the single headstone of two of Charles’ and Eliza’s infant children, which can still be found in Happy Valley Cemetery. Whilst the death of Ann in 1847 will have meant nothing to Harry, that of little Hughie, who died in February 1856, must have done so at the time. Writing to the children in England, Eliza had proudly told them of his arrival, but the news was followed immediately afterwards by another letter from Charles, telling them ‘the sad tale’ of the death of ‘their little brother’. Again, both letters have survived and must have been kept as a memorial of these sad events. Even if Harry remembered little of the detail and did not visit the grave, there was enough here to conjure up his parents’ presence and memories of the separation that had so marked his early life.[v]

After three years enjoying Hong Kong’s cosmopolitan world, Harry’s life changed abruptly when, in 1898, Britain acquired and then the following year, forcibly took possession of the New Territories. His efforts to prevent the removal of the Customs stations were unsuccessful and, as Commissioner, he was strongly associated with the aggressive approach which culminated in large-scale slaughter of the protesters. Heavily criticised by the Chinese, in the view of Sir Robert Hart, the long-serving Inspector-General of the IMC, Harry had to be replaced. Whilst this was made easier by the fact he was due to go on furlough, these events left a bitter taste for him and Maggie, which was only partially mitigated by the eighteen months they spent on leave in Lausanne and England.

For his son, Harold, who was seven years old at the time, there was no bitterness – the time in Hong Kong had been, he later wrote, ‘marvellously happy’, one in which they had been able to indulge in all the privileges afforded to middle-class western children in this colonial setting. What was ‘harrowing’ was the parting with their father when his furlough ended and he returned to China alone. Harold well remembered, ‘making a resolve that never would I be in a position where I must periodically leave my family and go away alone’. [vi]

Separated for much of the next seven years until she returned to China, Harry and Maggie shared their anguish in their letters – some eighty during Harry’s two years in Shanghai – which can be found summarised in his Letters Book. These also reflected the difficulties Maggie was experiencing in bringing up two boys of spirit, who hardly saw their father over these years. By the time he returned in 1911, the children had left school, and nursing a bitterness about his final years in the Customs, he had little desire to talk about China. For Harold, therefore, Hong Kong evoked memories of pleasure but also of pain: the happiness of those years contrasting with the pangs of separation, in a way that would later colour his relations with his own children.

These memories are, therefore, captured in letters and photographs and embodied in lieux de memoire that can still be visited. It is still possible to walk down Hillier Street, to see the children’s grave-stone in Happy Valley Cemetery and to take the Peak tram to view the Commissioner’s house on Mount Kellet. And when I do so, I can reflect on what I should have asked my grandfather about his memories and about what his parents told him of their life in Hong Kong.

Mediating Empire was published in April 2020. My Dearest Martha: the Life and Letters of Eliza Hillier will be published in the autumn by Hong Kong City University Press. For details, see andrewhillier.org.

*Images used in this post with reference starting with ‘Hi-s’ are from the collections of the Historical Photographs of China Project at the University of Bristol.

[i] Detailed references for this post can be found in my book, Mediating Empire, An English Family in China. 1817-1927 (Folkestone: Renaissance Books, 2020).

[ii] Hillier Collection

[iii] The originals, together with typed transcripts are held at the School of Oriental and African Studies Archives, London (SOAS), CWM/LMS, MS 381124/01, Correspondence of Eliza Hillier.

[iv] James William Norton-Kyshe, The History of the Laws and Court of Hong Kong from the earliest period to 1898 (Hong Kong: Vetch and Lee Limited, 1898), Vol. 1, p. 384.

[v] For the gravestone, see the illustration in Patricia Lim, Forgotten Souls: A Social History of the Hong Kong Cemetery (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011), p. 118. It is also referred to on http://Gwulo.com/node/8739, Inscriptions for Cemetery, Sections 01-09, Plot 09/08/18.

[vi] Harold Hillier, ‘Vita Mea’ (Hillier Collection), p. 9.