RESEARCHING MY HONG KONG FAMILY’S PAST:

A FOURTEEN-YEAR QUEST

(Part 1)

by an anonymous contributor

Vivian Kong has asked me to share my experience of researching my Hong Kong family’s past. As a graduate of Bristol University, I am more than happy to contribute to the Hong Kong History Project. My BA was in modern languages and my later PhD was in French. Eventually, with two published books, including a critical biography under my belt, I hoped that my academic training, despite not being in South East Asian Studies, would help me in the task of constructing a biography of my Hong Kong family. In the past fourteen years, I have had failures as well as successes and the failures will be a part of my story. Here I am going to set out some of the resources I have used in the hope that they will help other people. As websites improve, the element of human interface with Hong Kong officialdom – simple willingness to help – is deteriorating. It is important not to be deterred by that.

Family members, who could provide the richest vein of information, may prove impossible to unlock. If there is information that they wish to hide, they may refuse to share their memories. Because my father refused to discuss his Hong Kong past, I did not start my search until after his death. I was already in my forties before an older cousin, who had likewise waited until his parents were dead, made a start on our family history and asked me to review what he had written.

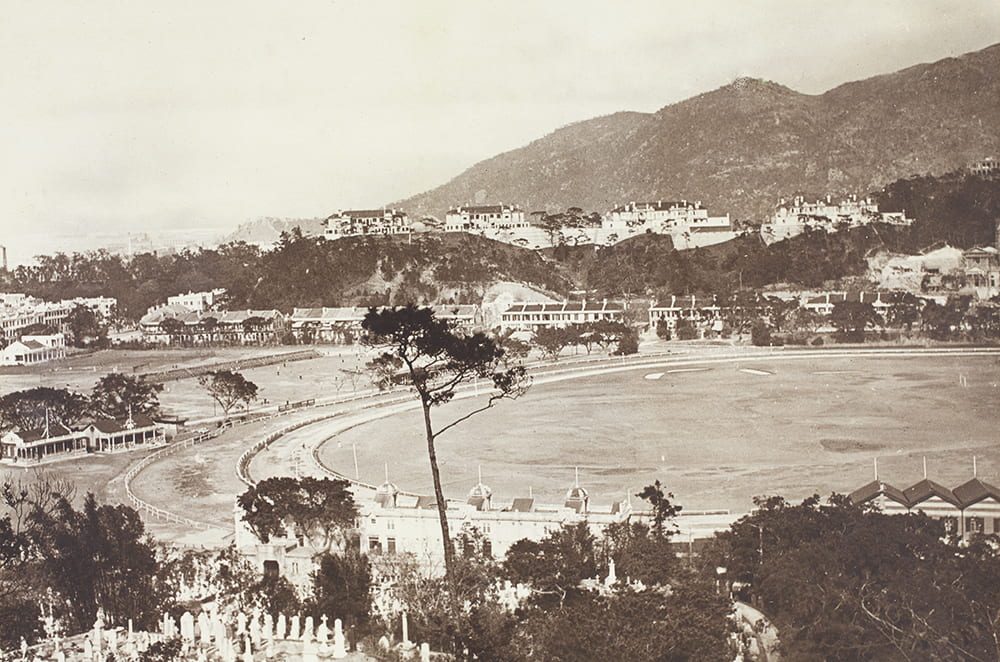

Four generations of our family lived in Hong Kong from 1866-1941, but were not spoken of. My generation only knew about our English grandfather, ninth child of a working class Northamptonshire family, who had arrived in Hong Kong 1895. We also knew that he had become an architect and created a successful business in Hong Kong, making enough money to build a magnificent house overlooking the Happy Valley racecourse. The story was that he had lost his fortune and that this loss had led to his premature death at the age of fifty-one. What we did not know was that our grandfather had married a seventeen year-old Eurasian girl, eldest daughter of a tavern keeper by his first Chinese wife (our great-grandmother). This is the secret that his children, including my father, successfully concealed. He and his brother and sister all married English spouses in England and revealed nothing to their children about their Eurasian heritage.

University of Bristol – Historical Photographs of China reference number: Bk09-29. Source: ‘Picturesque Hong Kong’ (Ye Olde Printerie Ltd., Hong Kong), c.1925.

Family research is a mixture of tedious work and chance. In my teens, I had asked my father to draw me a family tree.[1] Thus I knew the name of his mother, whom I always imagined had died young. Imagine my shock, when, aged fifteen, I received a memorandum recording a recent payment by my father to an Australian nursing home in her name, mistakenly enclosed in my parents’ weekly letter to me at my English boarding school. I returned it in my own next letter home, but my parents lived far away in Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and I received no further explanation from them. I recorded the event in my 5-year diary and tucked it away in the back of my mind.

In 2004 my older cousin unexpectedly died, but not before sending each of his three surviving cousins, myself included, a typescript of his painstaking work, to which we had each contributed the meagre facts passed on to us by our parents. After retiring from his job, my cousin, had begun by going through the copies of the South China Morning Post held by the British Library on microfiche (now microfilm). These give lists of passengers arriving and departing Hong Kong; weddings; obituaries; funerals; court cases; company advertisements; and lists of winners of sporting events. The British Library also holds the Ladies Directory of Hong Kong 1904-06. A supplement of the China Directory, it gives the residential addresses of the wives of all the Europeans living in Hong Kong. This can now be cross-checked against the Jury Lists partially published online by Gwulo and also available from the online Hong Kong Government Reports. The Government Reports also provide a wealth of information via a name search, if your relative had any official position whatsoever. It is easier to search for a man than a woman and, apart from three addresses listed against her name in the Ladies Directories, we found no information about our grandmother.

[1] He gave me a false English name for his Chinese grandmother. It is therefore advisable to use ancestry.com or findmypast.com for a more accurate account of descent.