Our guest writer this week is Chi Chi Huang, who recently finished her PhD at the University of Hong Kong. (Congrats Dr. Huang!) By incorporating archival research and the study of visual culture into her project, Chi Chi’s research explores how British popular culture imagined Hong Kong in the late 19th and the early 20th centuries. Here’s Chi Chi telling us how memories of her trips to Hong Kong as a kid influenced the direction of her research.

I was so excited for my first trip overseas. Mum packed a little goodie bag for me with a tube of Fruit Tingles (a real treat) and Pak Fah Yeow (白花油) (in case I felt sick). I had just turned six, I was going to Guangzhou via Hong Kong for the very first time since I migrated to Australia at the age of two. The trip started with a small hiccup – a delightful detainment at Hong Kong Immigration and Customs where I experienced two firsts in my life. I, (well my father on my behalf), applied for my first individual passport because my previous one was attached to my mother’s, hence the hiccup. And I experienced my first nosebleed. My Uncle swiftly came down from Guangzhou with copies of various documents demonstrating that I was, in fact, “Dao Zi Huang”, the name only my doctor would use. Soon enough, or soon enough in my memory, we were all skipping along on our merry way to Guangzhou.

My second trip to Guangzhou via Hong Kong lives in my memory with less enthusiasm. I was about nine and the previous year, I watched the Handover ceremony on television with utter confusion as to how one country in the first instance could rent a section of another country like you would an apartment or car. This time, the distance between Hong Kong and Guangzhou seemed further apart and littered with more barriers and checkpoints. I think this memory is less a comment of the changes that took place after the Handover, rather a reflection of the things I chose to pay attention to as a kid. In any case, I was not impressed. I simply could not understand why it was so hard to move around Canton!

These trips shaped my curiosity towards the city and ultimately the questions I asked in my PhD research. I grew up thinking of Hong Kong and Guangzhou as more or less one entity because, in my mind, everyone spoke Cantonese, enjoyed steamed fish with abandon, and ate wonton noodles. Once I started to grasp the concept of politics and diplomacy, I started to notice the differences between the two cities. When I was proposing a research topic, I was intrigued by what my friends knew and thought of Hong Kong and China, which seemed to mirror my own initial understanding. This led me to think about how cities shift in ones’ perception through experiences and exposure. Extrapolating from this, I began my research with the question “How did Britain perceive Hong Kong in the early colonial period, and how did this change over time?” Inevitably, this topic was too large, and I refined my core question to “In what ways was Hong Kong made to matter to Britain?”

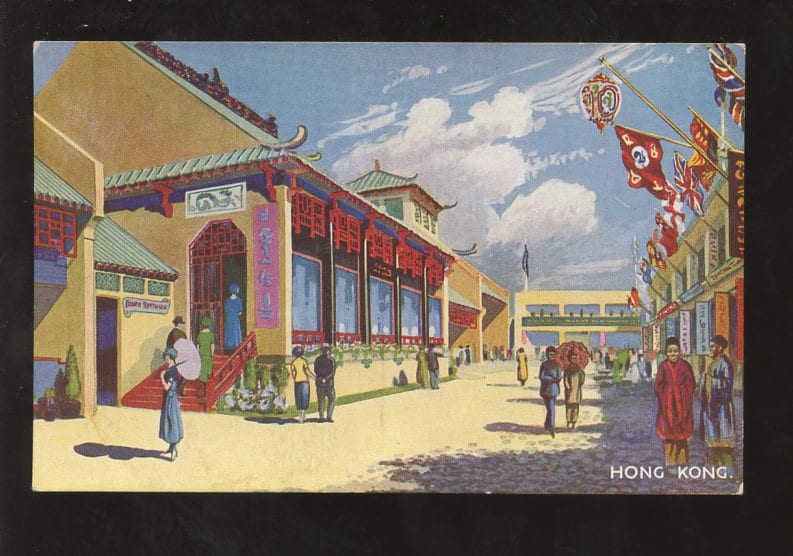

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the colony of Hong Kong had no discernible product or produce that was a quotidian feature of home life in Britain. The population in Hong Kong, whilst Chinese, wasn’t considered necessarily as intriguing as the more “authentic” visions that could be found just a few hours north of the colony. Hong Kong, however, was far from absent in British popular culture. In the various iterations of this public space, Hong Kong slowly morphed into a tropical ideal, in its geographical position, physical features, and social offerings. These ideals were, of course, in constant tension with colonial anxieties. But it is exactly in this tension that the value of Hong Kong as understood by individuals, scientists, merchants, and the colonial administration was expressed.

I am now contemplating how to turn my thesis into a book and I find myself wandering back to those memories and to the time when I conflated ideas of Hong Kong and Guangzhou. Before the outbreak of the war in the Pacific, Hong Kong was often talked about in relation to Canton, Macau, Singapore, Shanghai, Calcutta, Scotland, and even Budapest. Some of these connections are more obvious than the others, but it speaks to the malleability of how Hong Kong was perceived by the British. Perhaps the city’s current brand as “Asia’s World City” holds some historical truth, as Hong Kong refracted visions, aspirations, and concerns from across the globe.